|

| VOLUME I |  |

Chapter 1

The large black bird descended on the silent wings of her thoughts. Feathers fluttered fitfully for a moment, and her soul rippled swiftly outwards. Her presence permeated the void between the vibrating threads of the village's psychic quilt and her being soaked soundlessly into the weave of the world and becalmed it.

The old woman opened her eyes to greet the sun.

She sat quietly in the plaza and allowed the heat of the late morning sun to penetrate her thick robes and warm the aging muscle and bone beneath the black woolen cloth. Her skin was the colour of the desert sand, her face traversed by ancient wadis worn deep into her flesh by the winds of time. Though her head was covered according to tradition, her veil hung loosely from her neck, draped casually across her breast. Gnarled and veined like branches of an old olive tree, her hands rested in her lap wrapped around distaff and spindle, paused for the moment from spinning wool from the basket at her feet. A thick aromatic cloud of herbs and spices emanated from the terra cotta jars and hollowed gourds scattered on the ground about her, and from beyond the underlying cacophony of sounds bubbling madly from the neighbouring houses and shops, she sensed the slow majestic rivers of energy flowing through the earth beneath her feet. A fisherman returning from the river, trod softly and respectfully past in the course of going about his business, taking care not to allow his shadow to fall upon her.

Two small children entered the plaza, chattering in a secret childhood language. Their voices dropped to whispers as they approached the old woman and their step slowed until they stood transfixed before her, eyes filled with curiosity, wonder and expectation. The old woman opened her eyes and smiled at the youngsters, and as her gaze embraced them, a gentle breeze affectionately tousled their hair and hugged their tiny bodies. Animated by the touch of the wind, the two giggled and ran off, pausing only briefly to glance back at the woman before they disappeared around the corner of a nearby house.

The old woman rose and a small black cat uncurled itself indignantly from the folds of her dress and dropped soundlessly onto the ground, blinking as it emerged from a contented half-sleep twilight dream. It was momentarily indignant at being brought so quickly into the real world, then accepted the transition with feline equanimity and stared adoringly at the old woman, rubbed itself affectionately against and betwixt her legs, then wandered off, deciding to clean itself in the first warm sunny spot to take its fancy. The old woman stepped forward, her eyes fixed intently beyond the horizon to the west where she sensed a disturbance.

As her mind opened, the breeze became wind, raised the dust from the street and tugged at her robe, pulling toward the dunes of the desert and the hills beyond. The cloth across the entrance to her house flapped noisily in the wind, and a young woman appeared from the dark interior to fasten the writhing cloth to a nail in the wooden doorframe. The young woman stared curiously into the distant haze searching for the focus of the old woman's gaze, yet could neither see nor sense its cause.

"The child is coming, Yohanna," whispered the old woman excitedly. "The child is coming!"

"I will get your things, Grandmother," said Yohanna, then turned and disappeared into the dark cool interior of the adobe dwelling. Yohanna was a striking young woman. Tall, big-boned and muscular, she moved with the grace of a woman and the authority of a man. With no apparent effort, Yohanna gathered several bundles, already wrapped, and carried them through the back of the house and across the small sun dappled courtyard to the stable and deposited them on a crude bench outside the stable door.

She disappeared for a moment into the stable, then reappeared leading a small donkey. She tethered the animal to a pole supporting the wooden framework of the palm-thatched roof which spanned the courtyard. She threw a high pommeled saddle over the donkey's back, then hung a large basket from either side. Carefully, one by one, Yohanna packed the baskets with the bundles she had placed on the bench. After cinching the saddle tightly around the donkey's belly, she adjusted the balance of the baskets, and satisfied with her work, led the donkey through the gate into the street, where the old woman waited patiently.

"Yatpan is ready, Grandmother."

Yohanna offered her arm to the old woman and helped the crone step toward the donkey. Then, kneeling, she cupped her hands together and the old woman slipped her foot into them and Yohanna effortlessly hoisted her grandmother up onto the donkey's back. The crone gasped and laughed as she wobbled on the beast's back, then settled into the saddle and regained her balance and dignified composure. Silently, Yohanna grasped the animal's reins firmly and the two women turned their faces from the village, and began their journey.

Houses gave way to fields, and the old woman surveyed the countryside imperiously and contentedly, tallying each part of the passing landscape as a queen taking inventory of her holdings. The goats she noted. The sheep she noted and their shepherds. The orchards and vineyards and the workers in each. The fields, and the women gathering the harvest. Nothing escaped her eagle eyes. Fields and pasture yielded to the desert and the path became wilder. Inspired by the freedom travelling had brought her, she took a deep breath and began to speak.

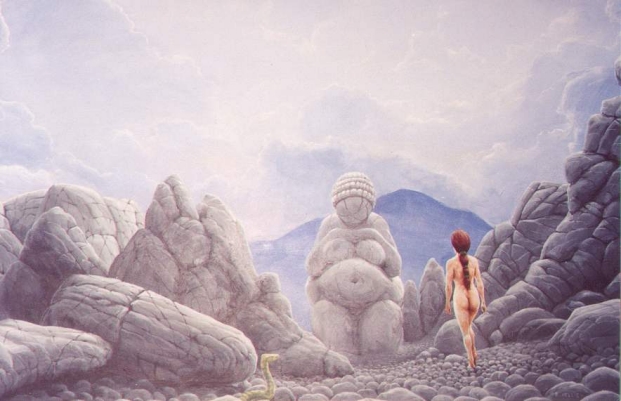

"Once Yohanna, there was no Beginning nor was there an End. Sweet and bitter mingled together for there were no senses to perceive them. No reeds were woven for no rushes sprang from the muddy water. No water flowed for none fell from on high. Even the gods were nameless and formless, for their destinies were yet to be decreed. No one counted the days for no Sun marked their passing. No one counted the months for there was no Moon. Before the time of Abraham and Moses, before the city of Ur rose from the Garden and turned it to desert, before even the Garden itself existed, at that time, there was only the Mother Without Form.

Then, somewhere, at some time, the Great Mother began to breathe. With her first breath she called the name Tia-Ma'at into the void. And from the second, the body of the Earth arose from the formless waters. From the third breath of the Great Mother, a vapour rose from the mouth of the Creatrix Mundi, Tia-Ma'at, and formed the Sky Above and the clouds within it. The fourth breath of The Great Queen Tia-Ma'at passed over waves of the Ocean and called out the names of every scaled fish, shelled animal, and whale, male and female, and they all came to Being. From the fifth the rain fell from the Sky, and brought into being by that same breath, Anu spilled his seed upon the Earth and from the womb of the Earth sprang the plants. Palms, olives and cedars sprouted and became forests; wheat, barley and grass for pasture burst through the red earth of Tia-Ma'at. From the sixth breath, the womb of the Great Mother opened wide and gave birth to all the animals, male and female: sheep, goats and cattle, lions, bears and wolves; and all manner of birds and insects. As the rain fell from the Sky, the rivers of the world sprang from the Earth and their rushing fingers reached to embrace the Sea. Tia-Ma'at passed over the Earth and from her seventh breath, called her people from the very stones of the Earth, both male and female.

Then, somewhere, at some time, the Great Mother began to breathe. With her first breath she called the name Tia-Ma'at into the void. And from the second, the body of the Earth arose from the formless waters. From the third breath of the Great Mother, a vapour rose from the mouth of the Creatrix Mundi, Tia-Ma'at, and formed the Sky Above and the clouds within it. The fourth breath of The Great Queen Tia-Ma'at passed over waves of the Ocean and called out the names of every scaled fish, shelled animal, and whale, male and female, and they all came to Being. From the fifth the rain fell from the Sky, and brought into being by that same breath, Anu spilled his seed upon the Earth and from the womb of the Earth sprang the plants. Palms, olives and cedars sprouted and became forests; wheat, barley and grass for pasture burst through the red earth of Tia-Ma'at. From the sixth breath, the womb of the Great Mother opened wide and gave birth to all the animals, male and female: sheep, goats and cattle, lions, bears and wolves; and all manner of birds and insects. As the rain fell from the Sky, the rivers of the world sprang from the Earth and their rushing fingers reached to embrace the Sea. Tia-Ma'at passed over the Earth and from her seventh breath, called her people from the very stones of the Earth, both male and female.

And still, even then, there was no Beginning and no End. Life was a Great Circle. So Tia-Ma'at, Mother of the Asura commanded, `Let lights appear in the sky to separate day from night and to show the time when days, years and religious festivals begin and end; they will shine in the sky to give light to the Earth.' And it was done. To separate light from darkness, Tia-Ma'at gave birth to twins, the Golden Goddess Shappash, the Sun, Luminary of the Gods, to rule over the day, and the God Sin, the Moon, to rule over the night. Tia-Ma'at was pleased with what she saw. So, evening passed and the first morning came.

A Great Serpent emerged from the womb of The Great Mother and each year devoured itself and was reborn. And the people measured the days by the passage of the sun, the chariot of Shappash. The children of the Great Mother measured the months by the passage of the moon, the chariot of Sin. But the years: the years were still not yet counted, for then, they meant nothing. Seasons did not yet appear for the bounty of the goddess was unhindered, and those who fell to the Earth were consumed by the Mouth of Tia-Ma'at and were born again from her Womb.

A Great Serpent emerged from the womb of The Great Mother and each year devoured itself and was reborn. And the people measured the days by the passage of the sun, the chariot of Shappash. The children of the Great Mother measured the months by the passage of the moon, the chariot of Sin. But the years: the years were still not yet counted, for then, they meant nothing. Seasons did not yet appear for the bounty of the goddess was unhindered, and those who fell to the Earth were consumed by the Mouth of Tia-Ma'at and were born again from her Womb.

In those times, the sheep and goats of Tia-Ma'at ran wild, and cattle roamed untended in great herds across the plains. Her people lived like great prides of lions in the wilderness. You can still see the circles of their ancient camp fires in the high places. Here, they sheltered in the sacred groves of the Great Mother Tia-Ma'at from the mid day sun, and nestled at night like doves in her leafy arms under the light of the Father Moon. Each day, the people gave thanks and left offerings to Tia-Ma'at.

Mothers, aunts, daughters, and sisters lived together like prides of lionesses. They gathered wild figs and dates, roots and berries and their children ran happily between their legs. The largest groves, around the water holes, were gathering places to tell stories and share what they had. Every where they gathered they formed circles, and the circles became their way of thinking.

There were men in the circles, too. They lay with the women when the women wanted them. They stayed for as long as they were useful. But men passed from circle to circle. When the boys became men, they left to join with women in other circles. Those who were not favoured as readily, because of physical deformity, or querulous nature, were not satisfied, and travelled alone or in small groups, hoping to find a circle which would accept them. Men thus rejected began to search for a greater meaning to their lives than that of consort to the Great Mother. Because they travelled from circle to circle, men thought of Life as a straight path, a journey between two points, Thus men conceived of a Beginning, and, of course, the End became a mystery to them.

But when a man left and hunted for meat, he saw Death at the end of the hunt, and so reasoned Death also was the End of Everything. Through death, he brought meat to the circle. In times of famine when the plant roots dried up, and meat was more important than the fruits and grains, the hunters favoured those women who had favoured them. So, the greater hunters were favoured by more women than men who were not. A man came to fell more important and more respected as a great hunter than as a man. It was not long before these men realized their greatest power was in killing, and soon Death and the Mystery of The End became the centre of the men's cult.

This is how it has been from those times. Women gain their glory from giving life. Men grasp at glory by taking it. It is why now, we can see a Beginning and we can see an End, and everyone, you and I, to this day, count the years.

At times, hunting parties encountered other camps of women, and they took them by force under threat of death. Soon it was necessary for women to always be accompanied by men to protect them from other men who could have a woman in no other way but by force.

In return for the protection, the men wanted the favours of the women they protected, and began to lose sight of why they were favoured. They began to believe their most important role was as protector, for that is the way they began to see themselves. If another man lay with a woman they were protecting, they felt they had failed, and were afraid they themselves would be killed or run off by the man who had slipped in under their very noses.

As we all know, one man could never control a crowd of women, so the men took one woman each under his protection, and agreed with one another no man could lay with another's woman. Of course, the women thought nothing of this idea and rejected it, but the men beat the women who did not obey the new law.

But the men could not enforce this law if they were to hunt, and this was a very important ritual for them. The hunt is the means by which a man believed he gained his worth. So they built little huts to keep the women in while they were gone, and forbade the women to leave while the men were away.

But the women came out of the huts and consorted with whom they pleased. Some invited men into the huts and the men returning from the hunt were angry, and beat the women who had lain with others. If a woman refused to obey the law, then the men returning agreed she would be put to death. Their law says she must be stoned, because the men did not want their spears and arrows to be cursed by taking a woman's blood.

Still the women blessed by the spirit of The Great Mother Tia-Ma'at within them would not bow down to the men, so the men told a story of a new god they had seen out on the plains who was all-powerful, more powerful than The Great Mother, Tia-Ma'at. He had killed the Great Mother, they said. Their god was invisible, and could see everything which happened on the whole Earth, a god who punished any transgressions of the law by smiting down the transgressor with a bolt of lightning.

The women laughed. `The Great Mother Tia-Ma'at has brought us the Water of Life and the Secret of Fire. She brings forth fruit from the fields and the forests. She is the World Tree, the Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowledge. The Fountain from which all Life springs. Your god can only destroy and kill and inspire fear. That is not real power. Love is the only force which can create and nurture. Where is the love in your god?'

The men protested their god loved everyone also, but the women laughed, for no god who demanded death could truly know Love. The men could not even tell the women the name of their god, and the women knew the men were lying. So the men built walls around the huts and posted hunters on the ramparts to keep watch both inwards and outwards. So some hunters became soldiers and since that time there have been armed men around our towns and villages.

Now the men outside the walls realized the only way to lie with a woman was to band together and form armies to break down the walls and kill the men inside and take their women by force. At the very heart of even the darkest soul of a man, he wants to be loved by a woman, for that is truly the only way a man's destiny can be fulfilled. And so for their need for women, men invented War. And their god demanded it of them, for the god was only appeased by Death. When there was no War, the men would sacrifice animals and sometimes people to the gods such was their god's thirst for blood.

The women knew there was no such god for he had no name. The men were afraid to tell the women the name of their god for they knew The Great Mother, Tia-Ma'at would utter it on the four winds and destroy their lie with her magic. The men were afraid of women's magic still, and passed another law against the invocations and prayers to The Great Mother. They tore down the sacred groves living trees and built phalli of stone to replace them. They said stone was stronger than wood and believed the phallus was greater then the Womb of The Earth. They did not see the Tree lives forever, not as a single stand, but as Life passed from mother to daughter. As always, the men worshipped Death and practised the taking of life everywhere people opposed them.

Sadly, to this day, a man must now impose his will by means of fear and violence instead of through love and honour. Fear makes the same sound in male ears as respect. Their ears are closed to the Song of The Great Mother and they have shut their eyes to Her Glory. Their hearts have become stone, barred to Her Love, their minds are closed to Her Presence, and their souls are dedicated to the Glory of Death. But, despite everything men have done to prove their independence, the very Essence of a man springs from between a woman's legs, a man still needs to be accepted as a woman's lover, his whole being still only finds true fulfilment in a woman's love, and his pride takes root only from reciprocated devotion to a woman.

To this day, their god still has no name.

And they still fear The Great Mother Tia-Ma'at, the Deiva of a Thousand Names."

![]()